Voyager 1, the most distant human-made object in space, has been transmitting nonsensical data since November, sparking worries about its operational state. While the potential compromise of Voyager 1 carries more emotional than scientific weight, given that the spacecraft has already achieved significant breakthroughs.

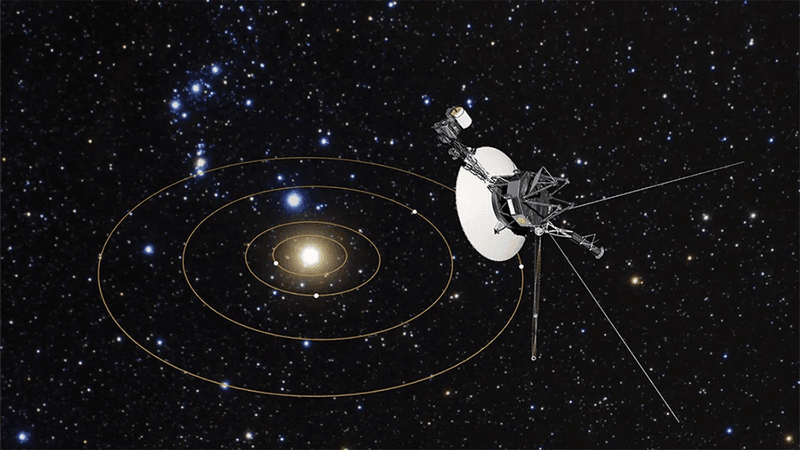

After nearly 50 years of space travel, NASA’s Voyager 1 has made history as the first spacecraft to enter interstellar space and remains the most distant human-made object from Earth. However, since November, it has only transmitted “incoherent” data to mission controllers, sparking debates about its operational status.

The potential end of Voyager 1 is seen more as an emotional blow than a scientific one. For the scientific community, the current situation with Voyager 1 is akin to observing an elderly relative lose their cognitive clarity. The spacecraft appears to have lost its way, and its transmissions no longer convey clear information.

Suzanne Dodd, the project manager for the Voyager interstellar mission at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory since 2010, told NPR, “It basically stopped talking to us in a coherent manner.”

Voyager 1, the inaugural spacecraft to exit the Sun’s protective heliosphere, has contributed to numerous significant discoveries. It detected a faint ring around Jupiter, unveiled two previously unknown moons of Jupiter, identified five new moons orbiting Saturn, and discovered Saturn’s G-ring.

Launched in 1977, Voyager 1, along with its twin Voyager 2, embarked on their mission to leverage a unique planetary alignment of the outer planets. This alignment enabled NASA to conduct a tour of four planets—Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune—in a relatively brief timeframe while conserving fuel. This specific alignment, which facilitated a spacecraft’s trajectory from one planet to the next without the need for substantial onboard propulsion, occurs approximately once every 175 years, last observed during the 1970s and 1980s.

In a somewhat unexpected sequence, Voyager 2 was launched earlier, on August 20, 1977, while Voyager 1 followed on September 5, 1977. However, Voyager 1 was set on a swifter and more direct path, allowing it to reach Jupiter by March 5, 1979, and Saturn by November 12, 1980. Voyager 2 reached these planets later, arriving at Jupiter on July 9, 1979, and Saturn on August 25, 1981.

Originally designed for a mission to just two planets and expected to last five years, the spacecrafts exceeded expectations. Following the successful completion of their primary goals, NASA engineers recognized the opportunity to extend the mission. They realized that with the ongoing success and durability of the spacecrafts, flybys of Uranus and Neptune, the solar system’s two outermost giants, were also achievable.

NASA has stated that the data gathered from just the Jupiter and Saturn legs of the Voyager mission would have been sufficient to significantly alter astronomy textbooks. However, the wealth of information sent back by the spacecraft over the past 45 years has dramatically transformed planetary astronomy and deepened our understanding of the solar system.

Shifting focus from our ventures into interstellar space to extraterrestrial objects reaching Earth, an intriguing event occurred in 2014. A meteor, later referred to as Interstellar Meteor 1, impacted Earth, landing in the Pacific Ocean. In 2019, a study led by Harvard astrophysicist Avi Loeb and astronomer Amir Siraj proposed that this meteor originated from interstellar space. While this assertion was met with skepticism by some in the astronomical community, Loeb participated in a 2023 expedition to the meteor’s suspected impact zone in the Pacific. There, he reported the discovery of materials he believes to be of interstellar origin.

The initial coordinates for the expedition were based on ground vibrations recorded at a seismic station on Papua New Guinea’s Manus Island, believed to be caused by the meteor’s impact. However, recent research led by Johns Hopkins University has presented a different explanation. The study indicates that the detected vibrations weren’t due to a meteor but rather were caused by a truck traveling on a nearby highway.

Furthermore, the study critiques Loeb’s findings, suggesting that the materials he identified are likely common meteorite fragments or byproducts of meteorite impacts on Earth, rather than substances of interstellar origin. Despite this setback in the quest for interstellar materials on Earth, humanity has successfully sent emissaries into interstellar space: Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, marking our presence beyond our solar system.